Hello and welcome to Another World is Possible! I’m Annette, mother, writer, and self-confessed selkie, living and swimming on the east coast of Ireland, and writing through the chaos to dare imagine a future more beautiful.

PS. This email might be clipped, so you may have to read it in your browser or in the Substack app.

Lately, I’ve been savouring, inhaling even, the softness of my youngest son’s cheeks, the warmth of his sleepy hugs, the smallness of his frame – he is the only one still shorter than me –, the sparkle of his big blue eyes. But he’s getting taller, his hand in mine bigger – when he lets me hold it. The other day, he asked about a spot on his chin. Oh wee man! B said with a wistful sigh when I told him.

Tears of sorrow pricked my tired eyes – for the end of our kids’ childhoods, the closing of this parenting chapter, and the hurtling into the teenage years, and how it’s both good and normal, and hard to let go.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines ‘matrescence’ as “the process of becoming a mother”, adding: “matrescence, the developmental phase of new motherhood, is like adolescence – a transition when hormones surge, bodies change, and identity and relationships shift.”

When my eldest son was born, we lived in London, far away from both our families. Matrescence felt like a dissolution – a falling through the floor in slow motion, desperately searching for solid ground, grasping for markers that proved reliable before, in life BC (that is ‘before children’), looking for directions, or at least a pointer, anything that would indicate which way was up.

I looked to other first-time mothers for cues and guidance, for empathy and sisterhood, for support even, but they were just as clueless and frazzled as me. It was peak Gina Ford craze1, and I stubbornly stayed away from it, turning to Dr Sears and attachment parenting instead. The only book I found on matrescence, even though it wasn’t called that at the time, was What Mothers Do: Especially When It Looks Like Nothing, by Naomi Stadlen.

We’re walkin’ a tightrope

High in the sky

We can see the whole world down below

We’re walkin’ a tightrope

Never sure, will you catch me if I should fall?

Tightrope, from The Greatest Showman

Fast forward fifteen years to the protracted, disorderly exit out of covid, and I watched them both, my eldest son and my daughter, slowly distance themselves from me and their dad. So far, so teenage-like, I thought with a heart-pinch, as they took increasing liberties in their socialising and sullenly withdrew to their bedrooms for ever longer periods of time.

It took a moment of crisis to realise that they had become ensnared in toxic friendships, and that what they needed was a hand, not our distant concern. They had fallen off the tightrope of adolescence, in the same way I fell through the floor into matrescence.

“Matrescence is not a process only experienced by new mums – it’s ongoing,”

writes in Matrescence is not a one-time event. “What’s required of us in our mothering is always shifting and changing as our children develop and grow. It makes sense that we continue to change and evolve alongside them.”Almost nineteen years into this mothering gig, I know this to be true. I may have found some stepping stones along the way, some branches to hold on to, but I’m still falling. It took time and a lot of emotional labour to rebuild the trust that was lost to those unhealthy relationships and my well-meaning, but ultimately mistaken, distance. As it turns out, they need me not less, but differently.

Too often, the conversation around parenting tweens and teens revolves around one question only, asked in hushed tones by parents of younger kids with a look of dread in their eyes: how bad is it? I know, because I used to be one of them.

The short answer is, it’s rarely plain sailing. Shortcomings that I thought were ancient history get laid bare; questions that I thought dealt with get raised again, and again; long-held assumptions get blown out of the water. For all that, we have never been so close, never talked and laughed so much, and it has everything to do with meeting them where they’re at, over and over again. And it has something to do with allowing myself to evolve and grow with them, even, god forbid, learn from them.

It’s a joy to watch them stretch and test their tender wings, and fledge, and still come back to base, their eyes bright with adventure and their wingspan grown a bit wider.

Turns out falling is a lot less scary when we do it together.

I’m proud of the mother I’ve become, of the mother I’m still becoming. But as Mothers’ Day2 comes round once more, hot on the heels of International Women’s Day, I'm left pondering what exactly it is we celebrate today.

While IWD prompted many a beautiful conversation about feminism with my 16-year-old daughter, Mothers’ Day is hardly likely to do the same.

“You’ve got your hands full!”

This is a phrase I used to hear all the time – every time I said I have four children; every time I answered the door to a salesman and the happy, noisy chaos burst out on the driveway; every time I renewed the car insurance and had to answer the dreaded question: “What is your occupation?”, and in a small voice I replied, “homemaker”.

“You’ve got your hands full!”

Every time, it felt like a judgement on both the size of our family and of my choice to stay at home with my children. Oh the shame I felt, still feel sometimes, for not only “not working”, but for conforming to traditional norms, thus not making the most of my education – for being ‘just a mum’.

The decision was made in the last month of my first pregnancy, some 19 years ago. Three weeks before my due date, standing with B on London’s Tooley Street after a quick lunch together, the words tumbled out of my mouth before I could really think them through. “When the baby is born, I think I’d like to not go back to work. Would that be ok?” There wasn’t much rational thinking involved and even less careful planning. Just this hunch that I wanted to be with my baby.

It was a choice, but a hard one to defend in this society of ours where your contribution only matters if it can be measured in cold, hard cash; where money is like a magic wand, granting value, visibility and power to whatever it touches. Deep down, I worried that being a stay-at-home mum be seen as a cop-out from real (paid) work and from feminism.

Back then, I said to my daughter about the late 1990s–early 2000s, back then, there was this assumption that feminism’s work was done. Women could now ‘have it all’. What I didn’t tell her was that, as a stay-at-home mum, I felt that I was letting the side down, if you will – a betrayal of my feminist ideals.

Truth is, even after all these years, I haven’t quite come to terms with my own life choice to be a “homemaker”. Hence my efforts through the years first as a blogger, then as a climate activist, to prove my enoughness, to justify my existence in a system that renders me invisible. I used to experience ‘mum guilt’ for often being physically present with my children but mentally absent, lost to the ‘blogosphere’. But does my work matter if it is not made valuable and visible by income? Is it really work even?

In France3, Mothers’ Day has a resolutely pronatalist history. First introduced in the early 20th century to boost the national birth rate, which lagged behind that of arch-enemy Germany, la fête des mères became official in 1926 to honour mothers of large families – after a whole generation of boys and men were lost as cannon fodder in the trenches of WW1. Quite the contrast with the day of peace and reconciliation envisioned by early advocates of Mothers’ Day in the US.

“Arise, all women who have hearts! Say firmly : Our husbands shall not come to us, reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause. Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy and patience. From the bosom of the devastated earth a voice goes up with our own. It says: Disarm, disarm!”

Mothers’ Day Proclamation, by Julia Ward Howe

The Mothers’ Day Proclamation, written in 1870, is a far cry from the tokenistic tribute Mothers’ Day has become, shamelessly commercialised by a culture of capitalist achievement that doesn’t care about what mothers do, only that we keep doing it, quietly and for free.

Yet this work that I do, unpaid, unseen and unvalued; the work that women do, in a society structured so that no good deed goes unpunished; what mothers do, especially when it looks like nothing, is a radical act of resistance.

My hands are not so full anymore. But as my children get older and become the kind of people our broken, breaking world desperately needs, I can say, hand on heart, that this work of mothering – the constant, silent, stubborn weaving of relationships and community that patriarchal capitalism sabotages at every turn – has been and continues to be my greatest contribution.

For Mothers’ Day, I don’t want afternoon tea or overpriced flowers. I want my kids’ homemade cards, their words, their hugs and kisses. I want to savour this day in their love’s spotlight, because they don’t take me for granted (well, unless it's about the laundry).

Mostly though, I want Mothers’ Day to be about liberating motherhood – which is to say, a day of protest and solidarity, for labour rights and reproductive health and housing and gender equality at home and in the workplace, about accessing the education, support and services our children need without having to beg or fight for them, about governments everywhere finally getting their finger out and addressing the epidemic of harm caused by smartphone use, social media access, screentime. I want Mothers’ Day to be a kick in the teeth (nah, in the balls) of the powers-that-be, corporate and otherwise. The day mothers’ work gets recognised for what it is, does, contributes.

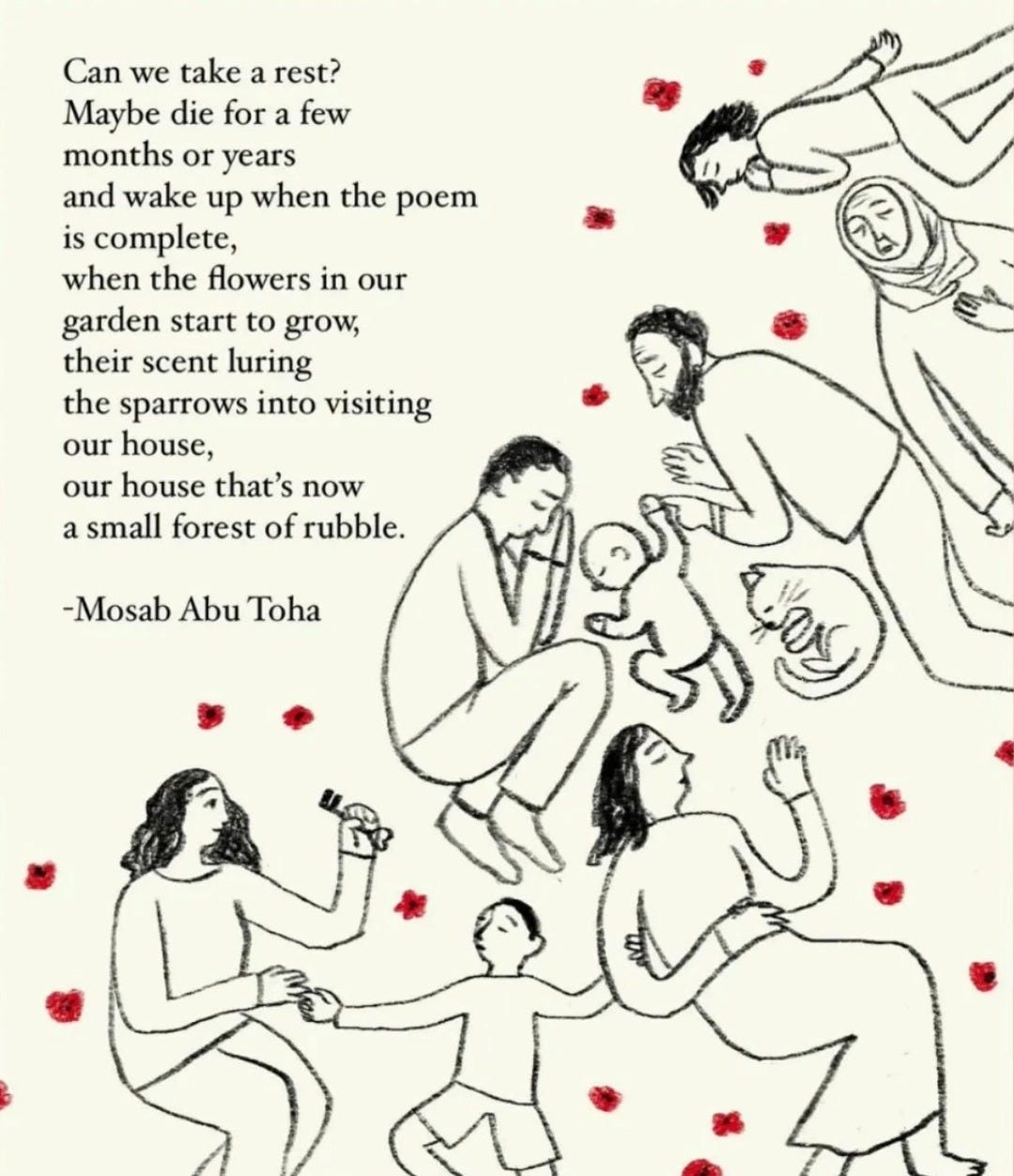

As the bombs fall again on the deliberately starved families of Gaza, as the worst among us slaughter and erase with impunity, making history even as they annihilate the future, please spare us your performative gratitude and glib inanities, your cheap cards and saccharine declarations about Irish mammies. Instead, let us make this the day we rise and roar, loud and clear–

Disarm! Disarm!

As ever, thank you for joining me here and reading my words – it truly means the world!

Much love,

Annette

My brand new offering, the SELKIE CIRCLE, starts on 8th May, and bookings are open now! Join this 7-week journey of 12 women seeking to reclaim their true skin and foster sisterhood, and shift from a false sense of inevitability to a grounded sense of agency – from ‘fuck no’ to ‘holy yes!’.

Will you swim in the selkie’s wake with us?

Feeling at home here and want to support my writing? Become a paid subscriber today to receive a signed copy of Sensual Soul Shine: the Reclamation of the Feminine (EU + UK residents only). Or you can opt for a one-off gift here.

You can also “like” my posts and comment (you will need to create a Substack account, with a username/handle and email address). For the most enjoyable reading experience, consider downloading the Substack app, so you can tap the heart icon, share on Substack Notes or other social media, and join in the conversation(s).

Disclosure: Buying any of the books recommended in this post may earn me a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Gina Ford is a former maternity nurse and the author of oft controversial parenting guide The Contented Little Baby Book (1999), which advocates a strict daily routine for both the baby and the parents. She doesn’t have children herself.

This is a post about my experience as a mother, not as a daughter, and I acknowledge how difficult Mothers’ Day is for many, many women, for reasons entirely different to mine.

In France, Mothers’ Day is celebrated on the last Sunday of May.

Oh Annette, this hit so so deep today. We've talked lots about the way we're parenting our teens, the joy and fun of it all amid the worry. The choices we made to stay home and how that often felt so undervalued and unseen. And that poem at the end... just wow. Such a moving, inspiring and beautiful piece. Off to hug my teens and spend the day in my garden. No afternoon tea here either!